PLUR1BUS, Explained (part 4)

Breakdown of S01E04, "Please, Carol"

Welcome to part 4 of a nine-part episode breakdown of the Apple TV series Plur1bus (pronounced “pluribus”). This post is spoiler-heavy. If you haven’t already and want to, go watch the show now and then meet Us back here.

Find previous installments here:

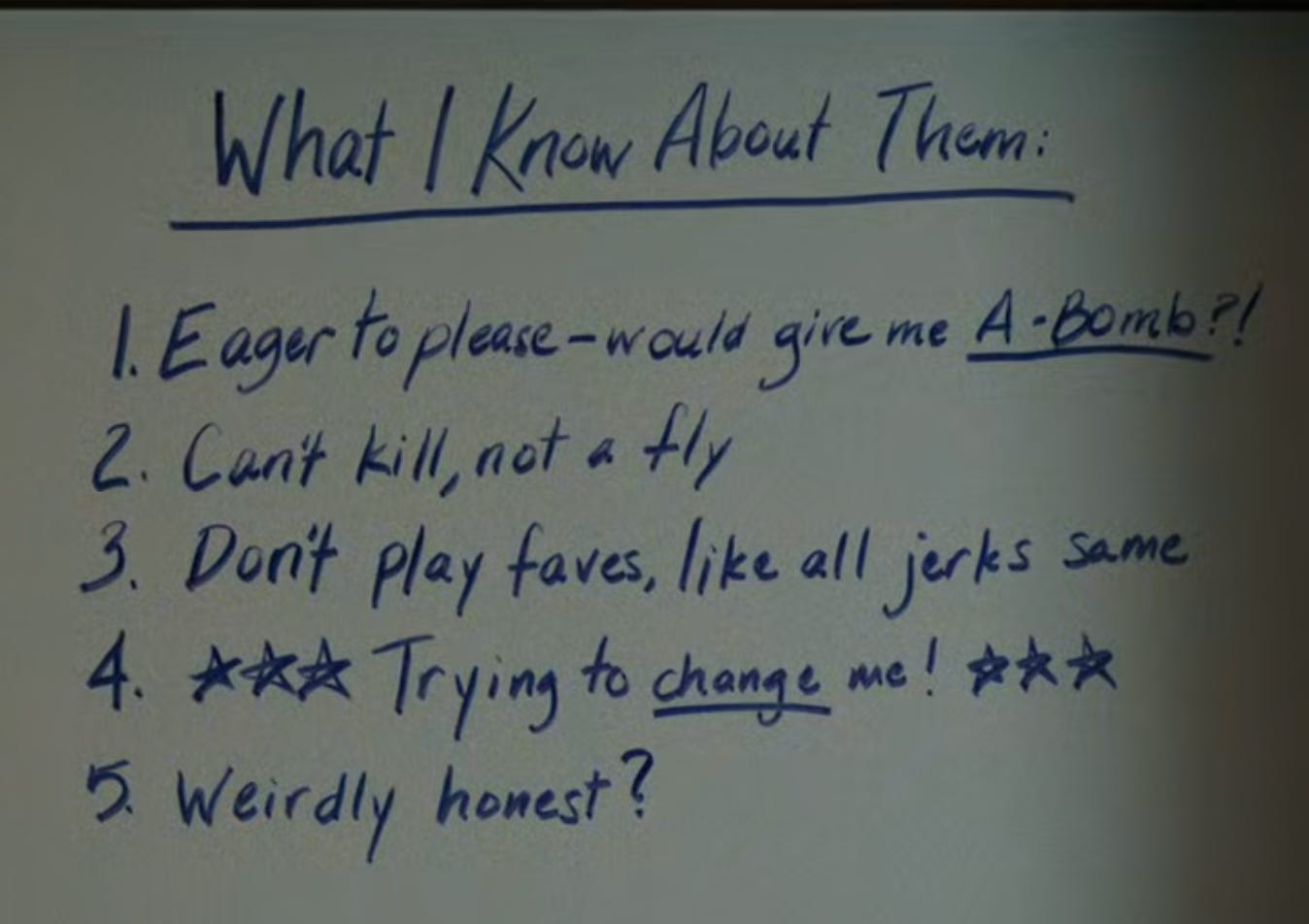

We’ll start with what We know so far, care of Carol’s novelist white board:

We can add the opening scene character Manousos (gentleman from Paraguay, played by Carlos-Manuel Vesga) to this list. Carol doesn’t yet know that he knows that she isn’t one of the Joined (that’s what We’re calling it now, btw, the Joined).

Early in the episode Carol asks Larry (Jeff Hiller), “do you like my books.” Larry gives a generic answer devoid of identifying characteristics. Carol then goes on to speak with Larry the way so many of us interacted with ChatGPT when it first became available.

Carol learns that one reader had planned to kill herself before she found Carol’s novels. Carol’s work literally literally saved this person’s life.1 Carol, a wealthy best-selling author, seems in search of validation—what more could she need?

“What did Helen think of my books?”

Well, there it is. That’s what more she needs. Instead of Our usual scene-by-scene breakdown, let’s linger here.

Carol finds out that Helen didn’t think much of the Wycaro series. The word Helen used was “harmless.” Helen loved Carol, and she loved the lifestyle that the success of the Wycaro series afforded them. Carol appears upset to find out that Helen has little respect for the series, and this might be surprising, because in Episode 1 Carol herself describes the series as “mindless crap.” Later in Episode 4, when Carol takes the Thiopental Sodium, aka “truth serum,” we learn that she actually thinks quite highly of her own work, implying that she puts on a façade of high-minded indifference for Helen. Why does she do this? Because she wants to be taken seriously as a novelist, and “serious” readers don’t give their attention to romantic sci-i (mindless crap). But, as we also learn, Helen thinks even less of Carol’s “serious” novel; she hasn’t even read the whole thing.

(We might wonder if this detail—the fact that Helen only read 160 pages of a 400-page novel draft, and that the remainder of the novel isn’t part of the Joined collective knowledge—might be a plot point later on…)

What artist—hell, what person—doesn’t seek validation, recognition, and reassurance from the people they love most? A person makes something—a book, a song, a meal, a chair, a bathroom renovation—and then turns to their closest people as first readers/listeners/tasters/sitters/bathers/etc.

“Honey, I made this, what do you think,” they ask.

What do you say? Often, you lie to them:

“It’s great!”

And you justify that lie by telling yourself that what you mean is that “it’s great” that they made something.

We’ve drafted several versions of this annotation, including one that goes on at length about an American Idol contestant who gives a pathetic audition.2 We keep coming back to the idea that dishonesty damages relationships. Even when we mean to use a lie to maintain a relationship, all it does is maintain the illusion of status. We lie because we are afraid of the negative consequences truth might bring.3 And then once the lie is told, confessing the truth becomes even scarier because now we have to contend with shame.

, who I’m convinced is a shadow writer on Plur1bus, offers a hypothetical scenario in which many of us might think dishonesty justified. Imagine you’re hiding Anne Frank in your attic. The Nazis knock at the door—or, oops. Sorry. Nazis don’t knock—the Nazis pound on the door:“Hello, Nazis here. Any Jews hiding in this house?”

Most of us would do what the Frank family’s real-life friends did and say, “No, of course not. No Jews here.” This would be a lie. Harris argues that the true moral answer would be, “You’re damn right there are Jews here, and if you take one more step, I’ll shoot you in the face, you Nazi bastard.”

You can see the dilemma.

The liar survives and the truth-teller almost certainly does not.

We want to survive. You want to survive.

Would we prefer a world of survivor-liars, or of the honest dead?

Good stories ask questions not easily answered.

Helen hasn’t exactly lied about Bitter Chrysalis, but she hasn’t been forthcoming either. In Episode 1, Carol asks, “Do you really think Bitter Chrysalis is that good?” Helen doesn’t answer that question. Instead she says, “I think people will love it.” Is that lying? Well, no, because who knows Carol’s audience better than Helen? She’s telling what she thinks is the truth, that people will love it. But her answer is evasive. Carol recognizes evasive answers from Zosia, but not from Helen.

Being a good person is really hard.

Before We go, a few words on the episode title, “Please, Carol.” This is the Joined chant from the end of the episode when Zosia falls into cardiac arrest. The Joined are literally saying, “please, Carol, stop being a damn idiot and let us save this individual.” The secondary meaning is the Joined’s objective: to make Carol happy, to please Carol.

A good title has at least two meanings, if not several. If we’re in the business of building titles, we might keep a catalogue of words with dual meanings, like “please,” for example.4

And finally, NM residents will already know that this really is the real mayor of Albuquerque, Tim Keller:

We might revisit the Barnes & Noble meet-and-greet scene from Episode 1. Carol has several lines reminding her fans of important details they missed in earlier Wycaro books, details that seemed like throwaways but were really setups for later payoffs…

“You’re not a good singer,” American Idol judge Randy Jackson tells the contestant who’s just croaked her way though “And I Am Telling You I’m Not Going,” the confessional classic famously sung by former American Idol winner Jennifer Hudson in the film version of Dreamgirls.

“But my family tells me all the time how good I am.”

“They lied,” Simon Cowell says.

“But why? Why would they do that?”

“Because they love you,” answers Paula Abdul, expertly choking back tears.

The American Idol contestant loved singing. If her family told her the truth, she might give it up, killing that joy (there’s a bigger can of worms here about the pleasure of singing and what it means to be a good singer and how mass media has changed the standards people set for themselves (a thousand years ago we compared ourselves to the best singers in the village. Now we compare ourselves to the best singers in the world…)). We don’t know yet if Carol actually enjoys writing, or how her skill might help save the day…

A few terrific titles: Art Objects, by Jeanette Winterson; Making Sense, by Sam Harris; (M)othering Children, by María Cioè-Peña; Here After, by Amy Lin; Light Years, by James Salter; Bough Down, by Karen Green; Still Moving, by Michael Sharick (imaginary unpublished novel in which a widow attempts to hide her husband’s moonshine machine but ends up cooking whiskey…); There There, by Tommy Orange; Good Will Hunting; Will and Grace; Grosse Pointe Blank; Arrested Development; Breaking Bad; Severance; Wicked For Good; Enemy Mine. Notice how all these titles have literal meanings and metaphorical meanings. Notice how many of these titles contain words than can function as both nouns and adjectives.

It doesn’t always work. Take Cider House Rules; are we talking about the guiding principles of the place where we make fermented apple juice? Or is the Cider House just awesome?

Are We saying that most titles aren’t very good? Yes. Yes, We are. But We could have it all wrong.

“ We might wonder if this detail—the fact that Helen only read 160 pages of a 400-page novel draft, and that the remainder of the novel isn’t part of the Joined collective knowledge—might be a plot point later on…)”—Good catch!