[An early version of this essay was delivered as closing remarks to Rat Fest 2023 in Philadelphia, PA. Rat Fest is an annual conference celebrating and promoting Critical Rationalist Philosophy. You can learn more at the Conjecture Institute website.]

(The title of this talk, as listed on the Rat Fest event site, is “Do I Think You Are?” This is a misprint. The real title was supposed to be “Who Do I Think You Are?” When I saw the mistake I decided to let it stand because both the original and the accidental revision seem to work, perhaps equally well, in different ways.)

On the first day of second grade, the teacher, a small woman called Mrs. Norton, asked me, in the wrecked voice of a heavy smoker, “do you want to be known as Michael or Mike?” At first I didn’t understand the question. Did I want to be known? I did! I was 7, but well aware of the concept of fame and its benefits. I had always been called Michael by family, teachers, peers. Here I was presented, all at once, with a rare chance to be taken seriously as a person with preferences, and the very new idea that I could have some amount of control over how I am perceived in the world. I didn’t understand the significance of the moment at the time.

“Call me Mike,” I said to Mrs. Norton, and so I was until junior high, when we realized that forty percent of the boys in school were named Mike, and we all started going by last names. The last thing you wanted to be was “one of the Mikes,” but that’s what I was until age 33 when I started grad school and a poet slapped a glossy name tag on my chest, the letters M-I-C-H-A-E-L spelled out in blue Sharpie. I suddenly realized how the extra syllable fundamentally changed the tone of the name. Mike, with a soft M at the top, and the hard stop of K, is working class, meat and potatoes, blue jeans pizza. Michael, with the sharp sound in the middle, and the soothing “uhll” to finish, is more sensitive, considerate, empathetic—linen shirts and kimchi tacos.

A name that we craft for ourselves might be the most visible sign of persona, of how we wish to appear to others. Personalities are complex. They are unpredictable. They evolve over time. A persona is not principally the product of evolution but of design. And because persona is a design artifact, it can be subjected to critique, just like a character.

A character is a design artifact. A character may resemble a person—that’s the whole point—but it is a mere collection of ideas gathered and tied together by people for a dramatic purpose. A character has no rights. Because a character has no rights, we can do with one as we please. A writer can bring great joy to a character, or a writer can cause a character to be burned alive. A reader can critique a character’s thoughts and actions without worrying about how they might feel, because they don’t feel, because they aren’t real. This is easy to see when we’re talking about a literary character who only appears in pages. The concept is more difficult to see when we’re talking about a film character who is played by a living actor. An actor is a person who has not been designed, and is therefore not subject to ethical critique.

Critiquing a person the way we critique a character is the number one danger of taking Literary Criticism too seriously, and taking Literary Criticism too seriously is one of the major missteps of Western Society’s Left Wing.

If you live in an area populated by members of Western Society’s Left Wing, you might see yard or window signs displaying some version of “In this house we believe that Science is Real, Kindness is Everything, Love is Love, Women’s Rights are Human Rights,” and so on. The last phrase on the sign is often “No Human Is Illegal.” We might find various arguments with most of the sign’s beliefs, but “no human is illegal” is perfect as is. Actions must have legal status, but a person must not. Shout this from the rooftops, all ye comrades, friends, and lovers: no human is illegal. And we might add, no person is wrong. That is, no person is incorrect, and no person is morally corrupt. An idea might be incorrect, and an action might be morally corrupt, but a person is not.

One of the highlights of Rat Fest 2023 was a talk given by Lulie Tanett incorporating a video clip of evolutionary biologist and world’s most famous atheist

interviewing a Christian political activist and creationist named Wendy Wright.1Dawkins and Wright argue over creationism and evolution, God and Darwin. It’s the sort of thing that plays well at a conference like Rat Fest, and we all enjoyed discussing it over margaritas and Manhattans. You can watch it here, if you like.

The video opens with Dawkins and Wright shaking hands in an office hallway. Dawkins thanks Wright for participating in the interview, and then asks, “where shall we go?” She gestures to a hallway corner and replies, “well, how’s this?” and then moves just a few feet. These are not real questions. The video wants us to believe that Dawkins and Wright are meeting each other for the first time, but they are not. This meeting is obviously staged. The conversation that follows is also staged, to a degree. Dawkins really does believe that evolution is the best explanation for the origin of species, and Wright really does believe what the Bible says. But what we see is theater.

I put it to you: we don’t see the real Richard Dawkins in that clip. I don’t mean that we see an impostor or a body double or a deepfake. I mean that there is a person in the world called Richard Dawkins, who walks around, draws breath, pays taxes, writes books—the person who invented the word “meme”2 in 1975, long before the internet. This person, Richard Dawkins, is also an actor who plays a character called “Richard Dawkins,” and we see the character in the video. The person Richard Dawkins has a personality known to his family and friends, and the character “Richard Dawkins” is a persona known to the world. The persona is a crafted and designed3 artifice performed and written by the actor, and in the case of what we saw, probably also a director and producer.

It’s important to notice the context of the Dawkins clip. The linked video is 10 minutes, but the full interview is over an hour. Short segments of it appear in episode 3 of a miniseries called The Genius of Charles Darwin, which first aired in August of 2008. What a strange decade that was, stuck between 9/11 and the ubiquity of the smartphone. In August 2008, America was just about to elect Barack Obama. One of the biggest influencers in that landmark U.S. election, and a perfect example of persona, is Stephen Colbert.

We know Stephen Colbert today as host of The Late Show on CBS.4 Back in 2008 he hosted a different program called The Colbert Report on Comedy Central. Some of us will remember The Colbert Report as pop art, parody of the highest order. On the show, Stephen appeared as an over-the-top conservative talk show host, who we could easily imagine on Fox News alongside 2008 contemporaries like Bill O’Reilly and Sean Hannity, or talk radio’s Rush Limbaugh. Colbert cheered for Republicans and ridiculed liberals. And but of course this was all a very obvious act. Colbert was pretending to be a conservative pundit. The performance was so exaggerated, so incongruent, so full of tonal dissonance, that we viewers could and were indeed supposed to see it as parody: Hey, look how dumb conservative talk shows are. This parody show has everything they have and it’s funny! There were some conservative viewers who mistakenly and naively thought the show was genuine. And there were many conservatives who knew it was all parody, but watched it anyway because there was no other good and funny comedy show that gave lip service to their ideas. The target audience—American liberals—knew that Colbert didn’t really believe the things he said on TV, because we knew we were watching a character clearly written and performed.

In 2015 Colbert took over for David Letterman as host of The Late Show on CBS. Gone were the wireframe David Deutsch5 spectacles, traded in for thick black geek chic glasses. Gone were the platitudes about American values. Gone were any references to Bill O’Reilly as Papa Bear, godfather of conservative media. Now, at last, we were getting the real Stephen, as he openly endorsed liberal causes and progressive agendas. Or so we were led to believe.

The truth is that The Late Show’s Stephen is also a character, only this time the audience isn’t in on the joke.

[Of course I believe that the real Stephen was upset that his show had been cancelled. And it’s also quite obvious that the outrage displayed on The Late Show the Monday after the cancellation was announced was performance. Colbert played angry because that’s what the audience wanted to see. That’s what made for good TV.]

So how do we critique “Stephen Colbert” or “Stephen Colbert” without critiquing Stephen Colbert? And what does any of this have to do with how normal people, non-celebrities, go around crafting personas all day every day?

I spent a lot of time with Sean Hannity in 2016, working as one of his audio technicians while he followed Trump around the campaign trail. I remember one time at the studio in New York, waiting for Sean to come in so we could start recording his Fox News TV show. Trump has said something particularly outrageous this day—maybe “shoot someone on 5th avenue,” maybe “grab ’em by the pussy—” I can’t remember. Sean is late. Producers are hanging out in the studio, which is a bad sign—producers hate the studio. I’m standing at the anchor desk holding a tiny lapel mike that I’ll clip to Sean’s jacket so that his words can be captured and broadcast all over the world. Suddenly the door flies open and Sean comes whirling in, papers and assistants trailing him. He tosses his briefcase to the stage manager, slides into his chair, takes a puff from an e-cigarette, and says something like, “okay now what should I think about all this?”

This is Sean the actor asking his writers what “Sean” the character will say on TV. They begin to discuss what his lines might be, crafting a narrative consistent with the persona, while the studio crew focuses lights and readies cameras. This is theater, through and through, no different than what was happening in Broadway theaters just a few blocks away.

I think we’re all doing this, all the time, to some degree. We don’t have writers and producers and assistance and an audience of 10 million like Sean Hannity, but we all have occasions where we ask ourselves, “what do I think about this?” or, rather, “how should I appear to think about this…?”

You might be feeling skeptical right now. Some of you are thinking, what the hell’s this guy talking about? I’m not a character. Well, you’re not wrong. And you’re not illegal.

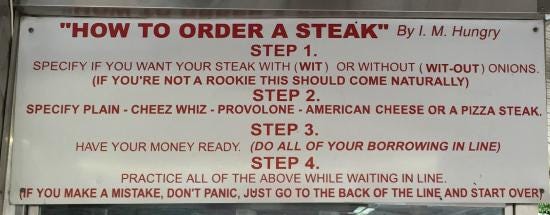

Rat Fest happens in Philadelphia, and one night we all go out for cheesesteaks at Pat’s King of Steaks.6 I love this place. I love a good snack shack with a too-small order window and steam venting from every port. Just above the order window is a sign, a list of instructions on how to order. I read the best one: “specify if you want your cheesesteak wit onions or wit-out onions,” and I realize that I don’t really know what a Philadelphia accent sounds like, so when it’s my turn to order I’ll use Brooklyn instead.

I rehearse in my head: “yo man, lemme get uhhhhhhhh, one cheesesteak, American, wit onions.”

Again and again, I run the lines, gotta get it right so the man in the too-small window will see me through the steam and think, what, I’m from around the way? Someone who can read a sign? Do they say “around the way” in Philadelphia? What the hell am I doing?

And then before I can match wits wit the cheesesteak man, Aaron (conference organizer number one) cuts in front of me, “this one’s on me,” he says, and orders for both of us. The man in the window asks, “you want onions?”

I came to Rat Fest, a conference on Critical Rationalism, not knowing what to expect. Everyone here is working on a big important problem. These people are physicists, mathematicians, musicologists; they’re thinking about epistemology, AGI, parenting philosophy. I’m just trying to convince people that writing is, first and foremost, for the writer, that it is communication with the unconscious mind. I don’t understand how to explain insight writing at this conference, or maybe I suddenly have zero confidence in the concept, and I end up disguising the topic to try and fit in. I’m a media studies professor, and a writing teacher. I came here to have meta discussions, so why is it so difficult?

While traveling to Philadelphia, with

(conference organizer number one), it became clear that the conference faced a few technical challenges, and that, because of my professional background, I could easily solve them. Very quickly I found myself running cables, making sure sound and video would work. This is not what I wanted to be doing.7 I didn’t know what to expect, but I didn’t want to be doing this.8Fuck, I thought. How did I end up here again? The last time I had been in Philadelphia was with Sean Hannity at Hillary Clinton’s Democratic National Convention in July of 2016, running cables to amplify the voices of others. That was where I decided to quit TV and find a job where people cared about the quality of ideas, not mere quantity.

While setting up, I am approached by

(conference organizer number two). I’ve got cables wrapped around my neck, a busted microphone in hand, tabs of gaffer’s tape hanging off my belt. He says, “hey, real quick, do you go by Michael or Mike?”“Which do you prefer?”

“Well, Mike is shorter.”

“Okay…”

What did I just do? Am I Mike for the next three days? I wanted to come here as Michael, as the kind of person who would be called “Michael.” But am I, after all, simply one of the mikes, some tool for amplifying someone else’s ideas? Am I Michael, right now, typing these words? Is “Michael” just a performance? Or merely a performance? Who do you think I am?

Who

Do you think

You are.

What a perfect name for a character who believes that Biblical creation is absolute truth. “Wendy” invokes the girl who loved Peter Pan, who ultimately left fantasy behind to grow up, regretting that choice every day of her life. “Wright” reminds us of “right,” of being correct, and of the American political right, of which Wright is a representative… To be sure, Wright was given her name by her parents, not a team of writers.

A Dawkinsian meme is a unit of culture in the same sense that genes are units of life. Memes are replicated and mutated as culture evolves, just as genes are replicated and mutated in genetic evolution.

You might be asking, “are you saying that we can critique “Richard Dawkins” all we want, but to critique Richard Dawkins would be a moral transgression…?” Is that what you’re asking?

On July 17, 2025, CBS announced that The Late Show would cease production in May 2026 just as Colbert’s contract expires. CBS claims that the show’s cancellation is “purely a financial decision,” while conspiracy theorists suspect that the real reason has to do with Colbert’s critique of Paramount’s $16 million settlement payment to Donald Trump. One suspects that we don’t yet know the truth.

British physicist David Deutsch is one of the intellectual heroes of the Critical Rationalist movement. I thought that I should probably sneak in at least one reference to him in my talk at Rat Fest, but no one laughed or even seemed to notice. David’s definition of “meme” makes more sense than Richard’s.

Sean Hannity would love Pat’s King of Steaks.

Not true. It’s what I said in the talk at the conference, but the truth is that I’m much more comfortable behind a scene than in it.

Yes I did.