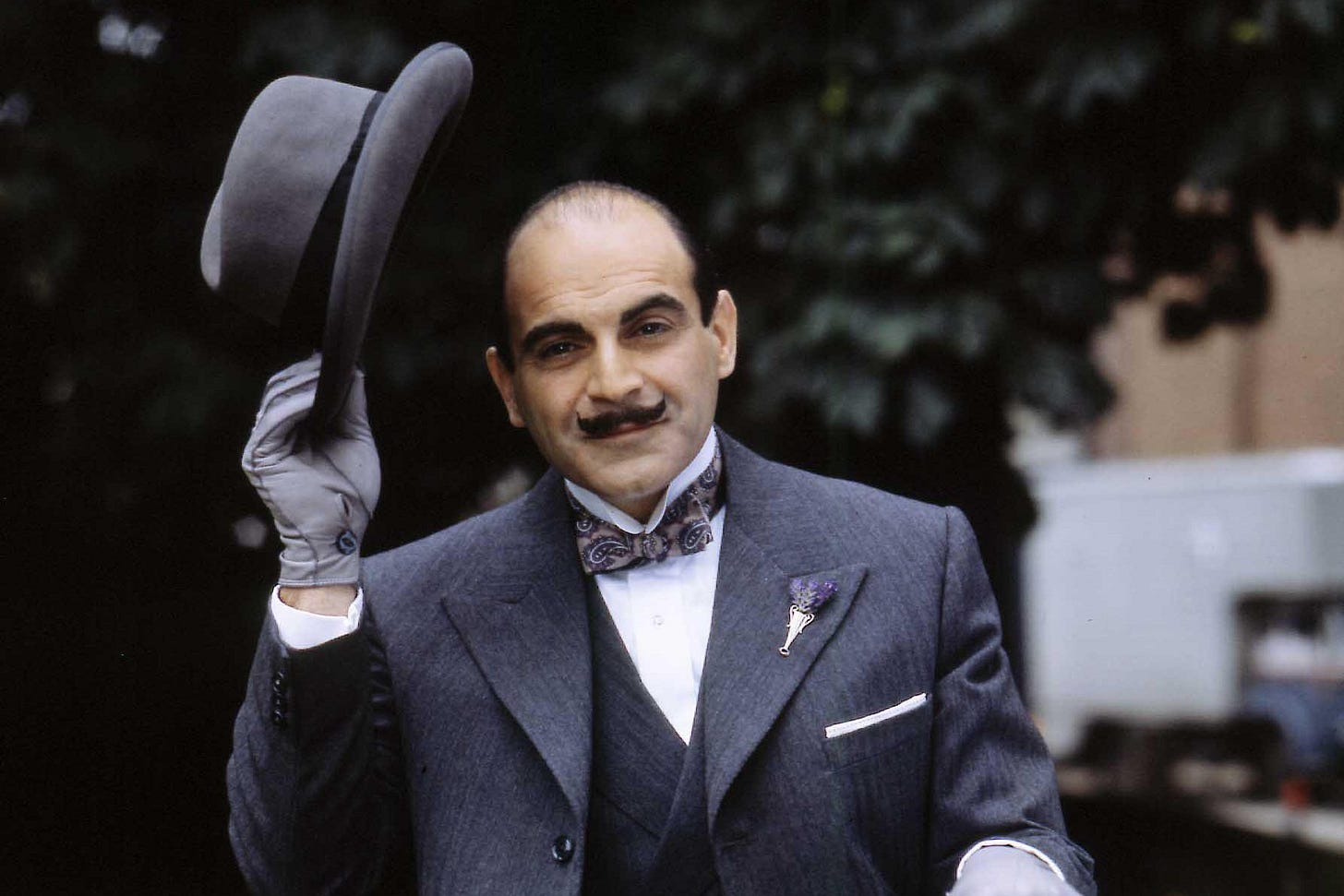

The actor David Suchet, who played detective Hercule Poirot in the British television serial Agatha Christie’s Poirot, between 1989 and 2013, tells an anecdote about filming on location in some tiny English village. He was standing on a corner in between takes, fully dressed in his Poirot costume—every episode is the same, by the way; the portly Belgian master detective Poirot, who charms the ladies and ridicules the men, is called in by local police to solve a murder case too complex for regular human minds—when an old woman, a local, walks around the corner, quite startled to see him.

“Oh!” she says. “Mister Poirot!”

Suchet is in character, and he doesn’t want to lose focus, so he puts on Poirot’s tight close-lipped smile, tips his hat, and greets the woman in his Belgian accent.

“Bonjour, Madame.”

“Well what are you doing here in Yorkchestervilleshire [or whatever the town was called…]?”

Suchet stammers a bit, “Erm, well—”

“Oh my God,” the woman blurts. “Has there been a murder?”

“Ah—”

“I never liked that vicar.”

“Um—”

“This bloody world!”

And on her way she went, muttering, “Poirot! Here! Wait’ll I tell my ’usband,” and Suchet shaking his damn head in disbelief, and proud of himself for not bursting her reality bubble.

Anecdotes like this—by chance a fan meets an artist whose work they adore, and what do they say?—I collect them. They cameo in various essays (Here, here, and here). I rewrite them to try and improve on the original storytelling. Until two days ago, I had no idea this was a constant motif in my pages, and I only noticed while editing a previous post. A reoccurring theme in one’s writing is like a reoccurring dream—it suggests an unresolved issue of some kind. In this case, there’s something about the way fans and artists interact that I find consistently interesting. It bugs me (in a good way). It’s itch that needs scratching. There’s some aspect of this kind of relationship about which I need a better understanding. I don’t know what the unresolved issue is, or why I need to keep thinking about it, but, now that I’m aware of it, I believe that I have a good chance of learning more about myself by writing into the idea.

Writing—that is, first drafting1—is like tilling up soil before planting. The rich nutrients are buried beneath the dirty surface, and they need to be exposed if anything is going to grow.

The dirty surface is the conscious mind—all the memories of the past, all the imaginations of the future, and any present-moment awareness to which we have immediate access. The dirty surface is what I call “I” and what you call “you.” The unconscious mind is the collection of memories and knowledge to which we don’t have immediate recall access. Maybe you know the name of your third-grade teacher. Maybe you remember the title of the first book your wife gifted you. Maybe you’re aware, even though no one told you explicitly, that there’s a link between the last day you saw that kid you loved, and the last day your mom saw that kid’s dad, whom your dad very much did not love. Maybe you’re aware of what you’re attracted to and why.

Or maybe you aren’t. Maybe you’ve forgotten. Maybe you’re happier that way. And but or maybe you need to till up the garden so something new can grow.

I don’t buy Suchet’s account. The way he tells it, the old woman had a screw loose, couldn’t tell the difference between television and reality. She thought, according to him, that even though the stories take place between 1935 and 1939, that Poirot was an actual person, living and working in her hometown. I don’t believe it. I don’t mean that Suchet is a liar. I think he just gets it all wrong.

I think the woman (was not old, no older than 50) knew exactly what she was saying. I think she, living in that small village, knew that her favorite TV show was coming to film an episode. She’s read every word Agatha Christie ever wrote: all the plays, Miss Marple, and of course her beloved Poirot, planning this encounter for years, decades. She comes around that corner, and here it is, this is the moment. In a split second she re-writes and blocks the scene for that specific piece of sidewalk, that specific angle of approach, with all her lines and timing. Here we go, it’s now or never, “Oh! Mister Poirot!”

What impresses me—and I’m just coming to realize this, through writing, that’s the point here—what impresses me is that this worked. She nails it. Dozens of potential points of failure in her plan to plot with Poirot, and nothing went wrong; it all worked. How many of us would choke, have choked. But even trained actor David Suchet, Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, even he doesn’t clock her performance.

Or maybe, wait, I take it all back—maybe what really interests me is how this woman chose to interact. She could’ve professed her love. She could’ve told him her favorite Poirot episode or novel. Instead she writes herself a part and joins the story.

The truth is I’m not yet satisfied.

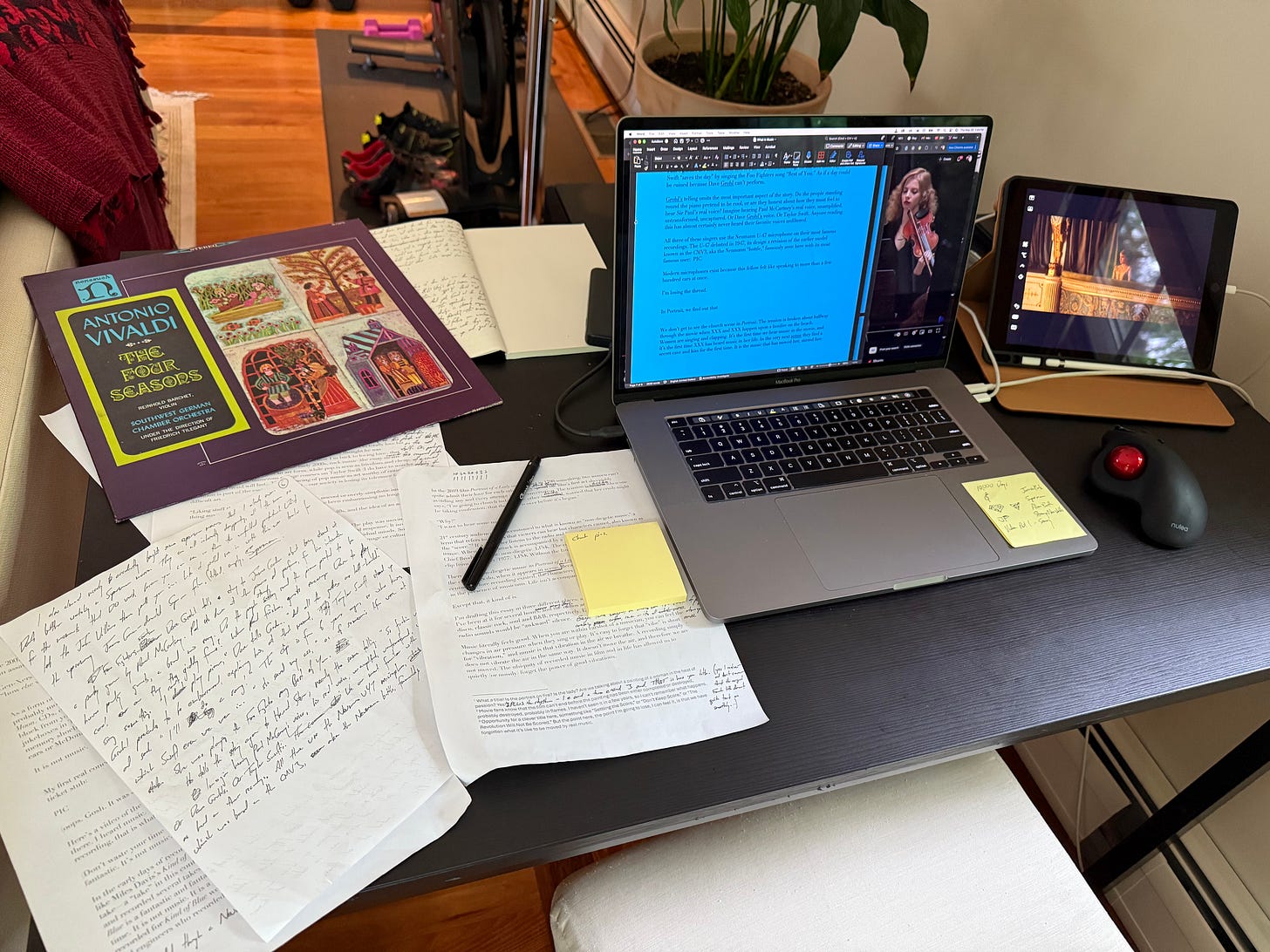

I’ve come to realize that most of the time, when I talk about writing, I’m talking about first-drafting. At some point I’ll tackle revision. I dislike the term “revision,” preferring “rewriting” or “second-drafting.” The long and short of it is that if you’re “revising” in the same Word or Google document where your first draft came to life, you’re doing it wrong. This is what my desk looked like while revising last week’s essay, and this is a poor example, with only very slight line edits from draft to draft:

Perhaps she was the better actor.